If you've been living in the same place for more than a year, your rent is almost definitely lower than what your landlord would charge someone to move in right now—by hundreds of dollars, in most cases. Sometimes thousands.

Rent control is great like that, for those lucky enough to still be covered under such protections in Ontario, but it does have a downside when it comes time to look for a new apartment: Sticker shock.

Roughly two years ago, in February of 2017, the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the City of Toronto was $1,620, up from $1,310 just six months earlier.

The same unit would now go for $2,270 per month, on average, according to Padmapper's long-running Canadian Rent Report, which analyzes rental data from hundreds of thousands of active listings across the country every month.

That's a hike of $650 per month in just two years, and it's safe to say that most renters haven't seen their incomes go up at nearly the same clip.

"Who's getting a $10,000 year raise?" says Amy Bath, urban planning buff and co-founder of the Toronto-based community building app Houndr.

"If you were lucky enough to find a really great rental say, four years to one [year] ago, you might be paying less than $2,000," she explained by phone. "So many people want move to a bigger space but can't stomach paying an extra 5, 6, 7, 800 dollars a month."

"We're at this crisis where people in their 30s are getting roommates again. I didn't think when I was younger... that I wouldn't be able to afford real estate at this age." - Amy Bath, 34

Bath, 34, now lives with her partner in a condo on Toronto's west side, but previously rented a basement apartment alone for $1,110.

"As soon as I moved out [the landlord] was able to rent it for $1,500," she says. "Four years ago, I was paying $1,700 for a 1,300-square-foot apartment at Bloor and Ossington above a Shoppers."

Few working milennials can handle $1,700 a month on their own without some serious sacrifices, let alone $2,260. This has led to many renters moving in with their partners to split the cost of a one-bedroom. Those who don't have such an option are forced to deal with what experts call the "singles tax."

"We're at this crisis where people in their 30s are getting roommates again," says Bath. "I didn't think when I was younger that that's something we'd have to be doing… that I wouldn't be able to afford real estate at this age."

"Condos used to be starter homes. Now, we can't even leave this particular condo based on the realities of renting right now. People are giving up the dream of having a single family home," she continues.

"I feel like our generation was promised something that's now deeply unattainable."

"The moment a sitting tenant leaves and vacates a unit, the landlord can raise the rent to whatever they like." - Bahar Shadpour, Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario

In 2018, the Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario (ACTO) published a report showing that more than 50 per cent of people in Ontario aged 25 to 34 rent their homes.

In Toronto, specifically, nearly half of all households are rented, and 46.9 per cent of those households can barely afford to pay the bills each month.

It's to the point where tenants are putting up with very poor living conditions so as not to disturb their landlords and potentially get "renovicted."

"You'll see a lot of people who are just kind of living under the radar because they're afraid of some sort of problem — it shouldn't be that way," says ACTO spokesperson Bahar Shadpour.

"If the landlord doesn't want to fix up the place to make it the best environment to live, eventually what ends up happening is tenants stay in those homes and take on the problems that come with a unit in disrepair. They're desperate."

Renovictions are a real concern for renters who know that their landlord could could claim their units for personal use, kick them to the curb, and then eventually rent the space for much, much more than rent control would have allowed.

"The moment a sitting tenant leaves and vacates a unit, the landlord can raise the rent to whatever they like, or whatever the market can pay," says Shadpour. "A lot of tenants feel like they're held captive in homes they found a year or two ago."

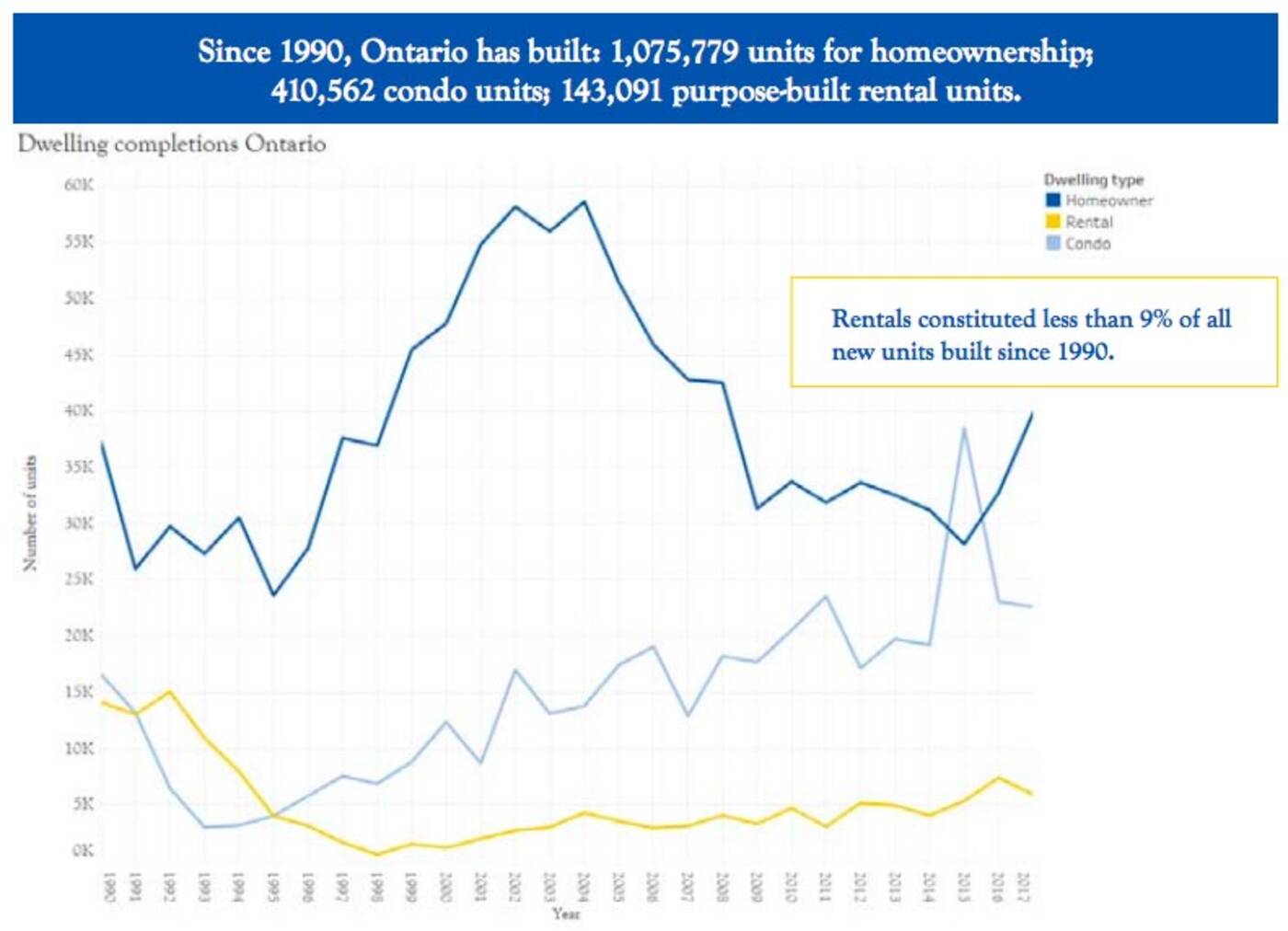

Experts say Toronto is in desperate need of more purpose-built rental housing. Image via ACTO using data from the CMHC Housing Market Information Portal.

For some of the city's more vulnerable residents, there literally isn't anywhere else to go once they lose their rent-controlled spots. For others, moving could mean being forced to leave the city, falling deeper into debt, or accepting that they'll never have kids.

"A lot of young people want to start families and they aren't able to. They can't afford homes to suit a growing family," says Shadpour, noting that those who choose to stay in their rent controlled units are smart.

"Rent for a new tenant is just ridiculous," she continues. "Young people, students, working professionals, they definitely aren't able to rent a new place."

Sure, there are options for young adult renters, but you can't just "buy a house in the suburbs" after spending every penny you've earned for the past five years to simply get by in Toronto. Nor can many young people even find jobs in their fields outside of the city.

And forget about buying (without a down payment from your parents, that is).

"If you weren't fortunate to buy like, five years ago, buying now is almost impossible," says Bath. "We just have no options other than to rent because nobody can afford to buy."

"The reality is that this is our future, from any perspective; environmental, financial," she continues. "We're not all moving out to a suburb and living that life. This is our new life, we have to figure out how to adjust our expectations to accommodate basic reality."

That, or we need to change things in terms of urban policy at every level of government.

I remember, 15 years ago or so, choking on the idea that condo prices were starting in the mid-$200k range. #TorontoHousing pic.twitter.com/cq5lwOtTJy

— Rebecca Pinkus (@GreenspaceGirl) February 17, 2019

Both Bath and Shadpour agree that one of the major drivers behind Toronto's affordability problem is a lack of purpose-built rental housing (read: apartments) in the city.

"From 1990 to 2017, out of all the units of housing built in Ontario, less than nine per cent were purpose built rentals," says Shadpour. "Condos are an important part of the rental market today, but they're not a replacement... they're owned privately—there's no security of tenure."

Not that Toronto even has enough condos for rent to accommodate its booming population very much longer. With the GTA's population expected to reach 9.7 million by 2041, we're in desperate need of places for people to live.

"There's a lot of debate going around about how we increase supply," says Shadpour, pointing to things like tax breaks for developers, rezoning neighbourhoods for higher density and providing surplus land to developers in return for a certain percentage of affordable rental units, as seen in Toronto Mayor John Tory's recently-approved Housing Now initiative.

"But one major thing we need to recognize here is that developers are not going to build affordable rentals out of moral obligation. They're in the business of making profits," she says.

Hence the need for measures like provincial cost-matching of Canada's $40 billion National Housing Strategy funds and recognizing the right to housing as law.

"We are hopeful that our federal and provincial governments can work together, set aside ideology, and take bold actions based on evidence," Shadpour continues.

"It'll take a lot commitment, but we can fix this issue."

by Lauren O'Neil via blogTO

No comments:

Post a Comment