Moss Park may only span the entirety of two blocks, but the neighbourhood’s name is known citywide.

It’s not the good kind of recognition: this rundown area in and around its namesake park—a barren piece of green space which runs between Jarvis and Parliament from Dundas down to Queen—is known to be a hotbed for crime.

The Moss Park neighbourhood spans the areas between Jarvis and Parliament between Dundas and Queen.

If you’re heading west toward Schnitzel Queen or Enat Buna, you’re more than likely to witness an illicit lunchtime drug deal as you pass the corner of Queen and Sherbourne, where groups gather day and night, in all temperatures, outside the Moss Park Discount Store.

Further north past the Followers Mission just steps from the giant Dollarama, the Salvation Army-run men’s shelter Maxwell Meighen Centre is sure to be fronted by at least several people lingering in the doorway, trying their luck for the services offered.

The neighbourhood is largely consists of low-income residents and shelters.

With the cold lines of the Moss Park Armoury making up its backdrop, there’s no pretence around the stark divide between this part of town and Toronto’s flourishing Garden District, just further west closer to Church, where students and new businesses abound.

It’s a different story for the majority of businesses on this end. Longtime businesses like Woven Treasures, which has been selling Persian rugs for over 24 years, is slated to close sometime soon due to rising rent and diminishing business, says the owner.

Longtime Persian rug purveyor Woven Treasures will soon close due to rising rents.

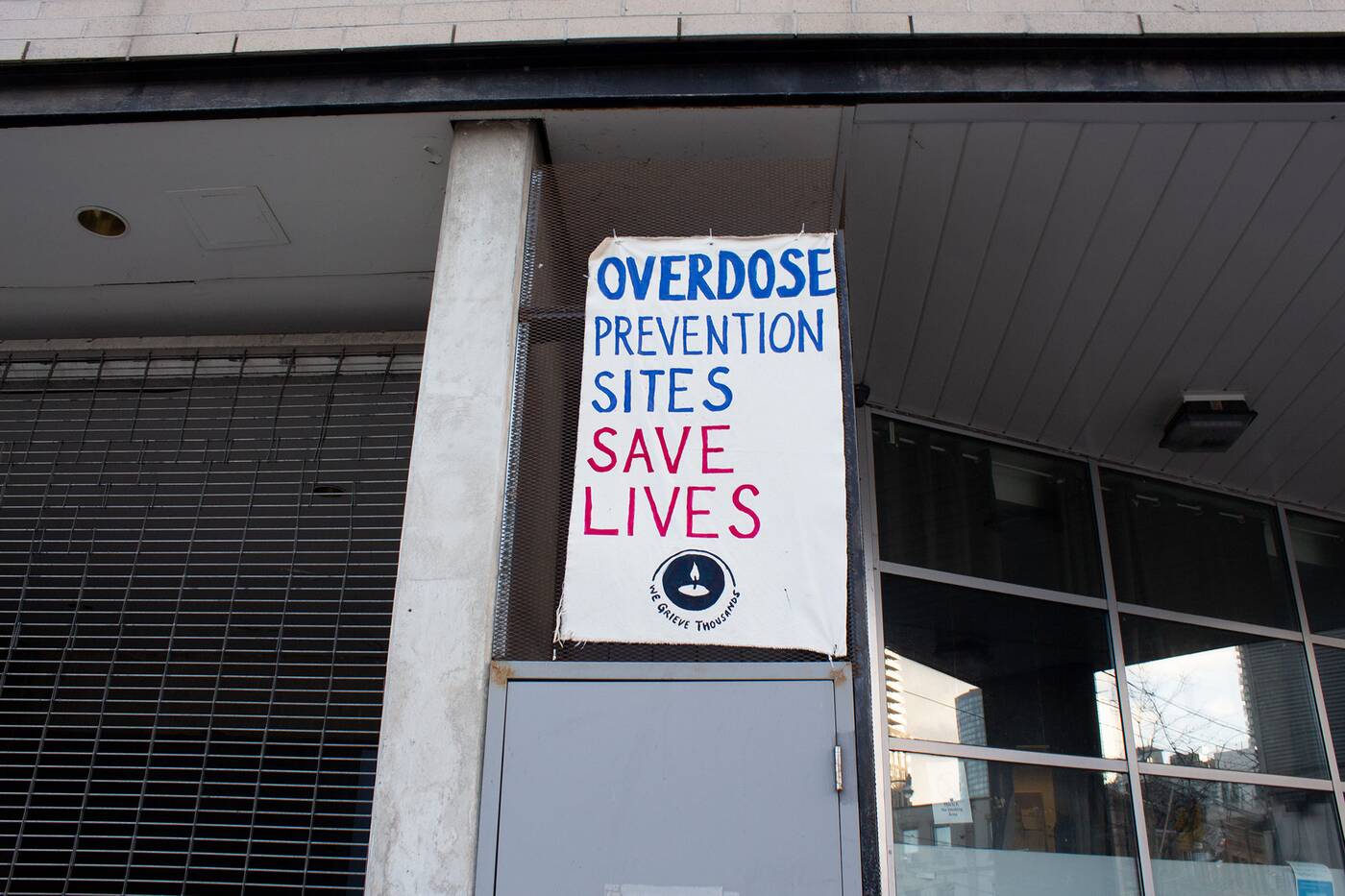

It wasn’t always like this: according to some longtime residents, the area has degraded noticeably over the past decade. The increase of drug litter, open drug use, and more recently, the introduction of deadly bootleg fentanyl in street heroin, sparked the creation of the unsanctioned Moss Park Overdose Prevention Site (OPS).

But the decline can even be dated back to the construction of the Armoury in the 1960s, which saw an entire strip of shops torn down to make way for the Canadian Forces facility, along with housing run by the Toronto Community Housing Corporation.

This massive change solidified, perhaps intentionally, Moss Park’s identity as Toronto’s carefully quarantined area of social inequities.

The Armoury was built in the 1960s.

Meanwhile, a few shops like Longboard Haven and the apothecary Leaves of Trees have carved out spaces for themselves as niche purveyors facing Moss Park directly, creating a surprisingly sturdy frontier of local businesses trying to make it in an area with low foot traffic and a bad reputation.

“Once we moved into the location we started to see how amazing the neighbours are,” says Randy Spearing, owner of the newest store on the strip, Department Store. “Everyone is really committed to the neighbourhood and seeing it thrive.”

Department Store opened in late 2018.

Opened in late 2018, Spearing’s pop up-turned shop specializes in locally-made goods like printed city maps, accessories, and stationery that seem more fitting for West Queen West than Moss Park.

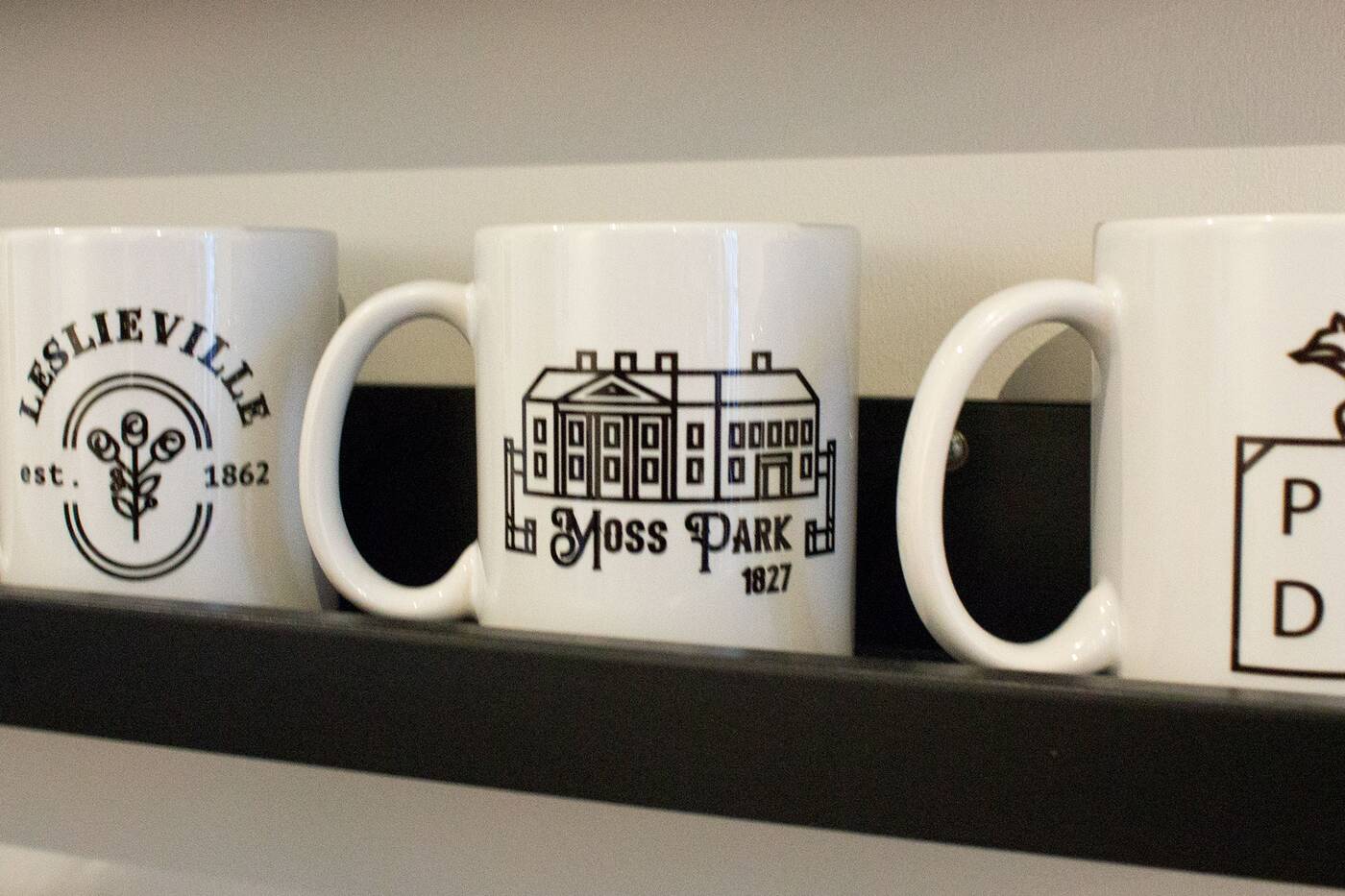

Perusing through its stylish stock of neighbourhood mugs and calf leather wallets, there’s an obvious disconnect between the store, which sells home goods, to the street it sits on, which is rife with homelessness and addiction.

The store sells an assortment of maps and gifts, like Toronto neighbourhood mugs.

“I do recognize there is a disparity between the people that live in the area and the goods that we sell,” says Spearing. “That’s a balancing act as a business owner...we don’t want to come in and displace people.”

Unintentional as it might be, displacement in Moss Park is well underway, and the businesses that have held out here will benefit greatly from its fast-approaching transformation.

A trio of condos is slated for the southeast corner of Queen and Parliament.

East of Department Store at 245 Queen St. East, three condos and a brand new park are taking shape. Towering at 24, 28, and 37 storeys each, the residences by ONE Properties have been approved by the City.

The project has already been scaled down significantly, but it’s expected to add a total of 1,468 new units across from Moss Park’s most illicit corner.

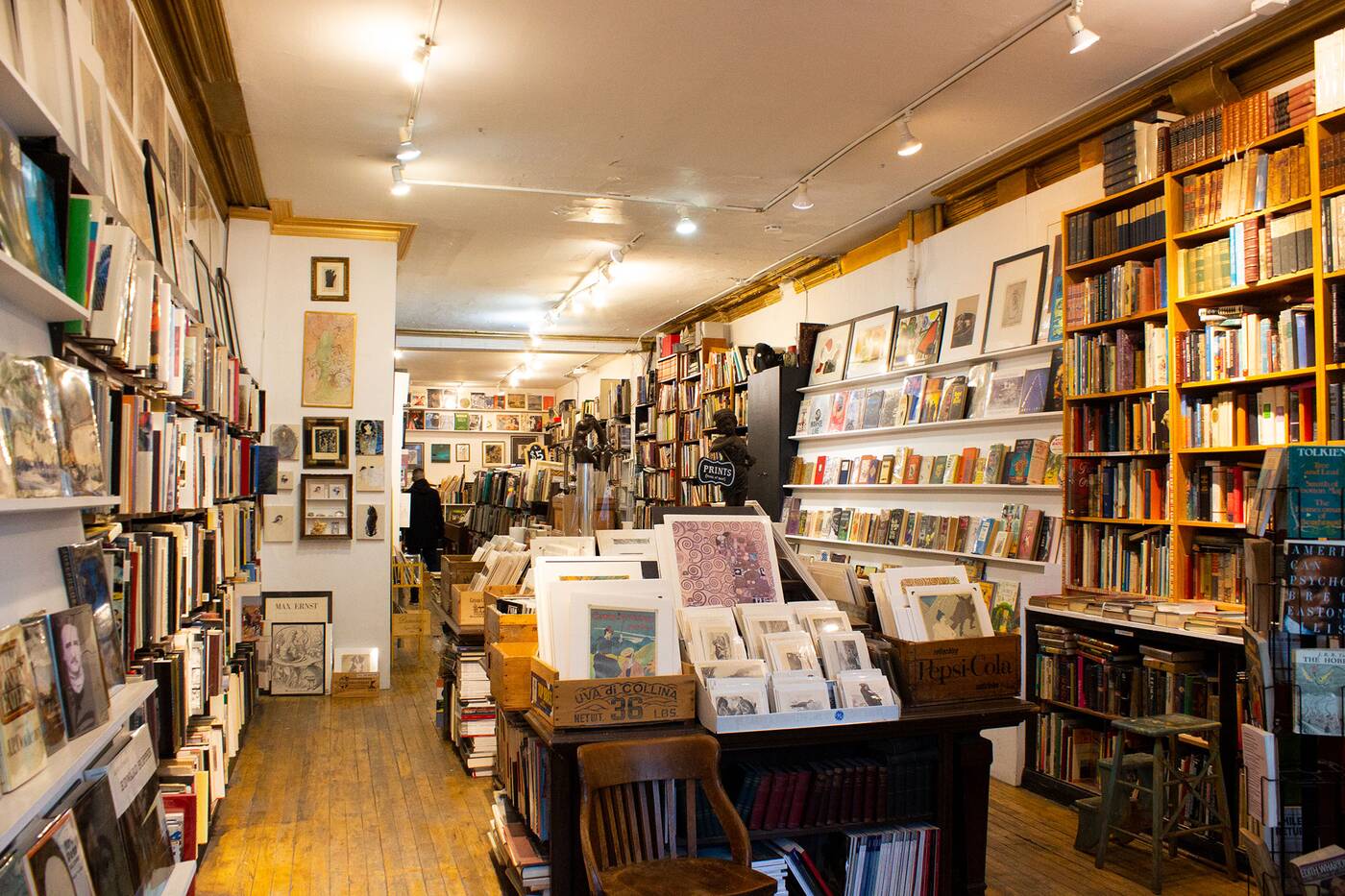

It’ll sit directly across from a row of heritage buildings housing businesses like Acadia Bookstore, which has been around since 1931 (it was called Jack’s Bookstore until the early 1960s).

Acadia Bookstore has been around since 1930s, and its owner is not looking forward to the new condos.

Selling two floors-worth of dusty books covering everything from art to the occult, the store barely sells to locals—most of its clientele comes from areas like Leslieville.

Even still, Acadia’s owner, who didn’t want to be named, calls the condo developments “a monstrosity”, and predicts the bookstore will have two years of success before their rent is jacked up.

It’ll be years before the developments are complete, but by the time it’s done, Moss Park will inevitably be flooded by a demographic far different than the one that resides there now, with the social capital to affect change on how the neighbourhood operates.

Moss Park's Overdose Prevention Site is one of the foremost social services operating in the area.

“One of the things that happens with those developments is that people with considerable wealth come to the area and want to change it,” says Jen Ko, a coordinator at the Moss Park OPS.

After nine months and thousands of controversial supervised injections operated in outdoor tents, Moss Park’s OPS finally moved into a permanent home at Queen and Sherbourne and now operates an outreach team to bridge the gap between locals with neighbourhood clean ups.

There have only been a few neighbour complaints over the past years, says Ko, but the majority of people living nearby understand the need for an OPS in an area like Moss Park. That likely won’t be the case with over 1,500 new residents in the area who will probably be paying upwards of $1,200 a month to rent a unit.

There have only been a few neighbour complaints over the past years, says Ko, but the majority of people living nearby understand the need for an OPS in an area like Moss Park. That likely won’t be the case with over 1,500 new residents in the area who will probably be paying upwards of $1,200 a month to rent a unit.

“I hope that folks who move into the neighbourhood do their own due diligence and learn more about the neighbourhood, and come into it with an open mind.”

by Tanya Mok via blogTO

No comments:

Post a Comment