The R.C. Harris Water Treatment Plant may be one of four city plants providing clean water to Toronto, but it is undoubtedly the largest and most prized of them all.

Sitting on a hill that ascends from the most eastern end 0f Balmy Beach, this cluster of Art Deco buildings endures as one the city's most precious structures for more reasons than one.

The R.C. Harris Water Treatment Plant was completed in 1941.

Its most obvious purpose: this sprawling plant cleans and produces more than 950 million litres of clean water daily.

What that boils down to is roughly 45 per cent of our water: without it, Toronto and parts of York Region would be short nearly half of its drinkable lake liquid.

The sprawling Art Deco property has been designated an historic site by two different organizations.

The sheer immensity of that volume is staggering, but even more so when you put together that, of Toronto's four water treatment plants, it predates the others by at least 20 years.

The Filter Building is accessible to the public during Doors Open Toronto.

But it's not the plants filtering capabilities which have captured the city's imagination with its nickname, The Palace of Purification, or transformed its impenetrable wall into the face of multiple movie prisons, or made it the backdrop for Ondaatje's Toronto epic, Skin of a Lion.

A series of underground pathways connect all three buildings together.

Designed in the 1920s and completed in 1941 to address unclean water and shortages throughout the city, the R.C. Harris represents the rare balance of a structure that is as beautiful as it is useful.

Dubbed an historic site, both by the Ontario Heritage Act and the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering, it takes its name after one of Toronto's public works commissioners: Rowland Caldwell Harris, a man who left behind a 33-year civic legacy that includes the North Toronto Sewage Treatment Plant and the Prince Edward Viaduct.

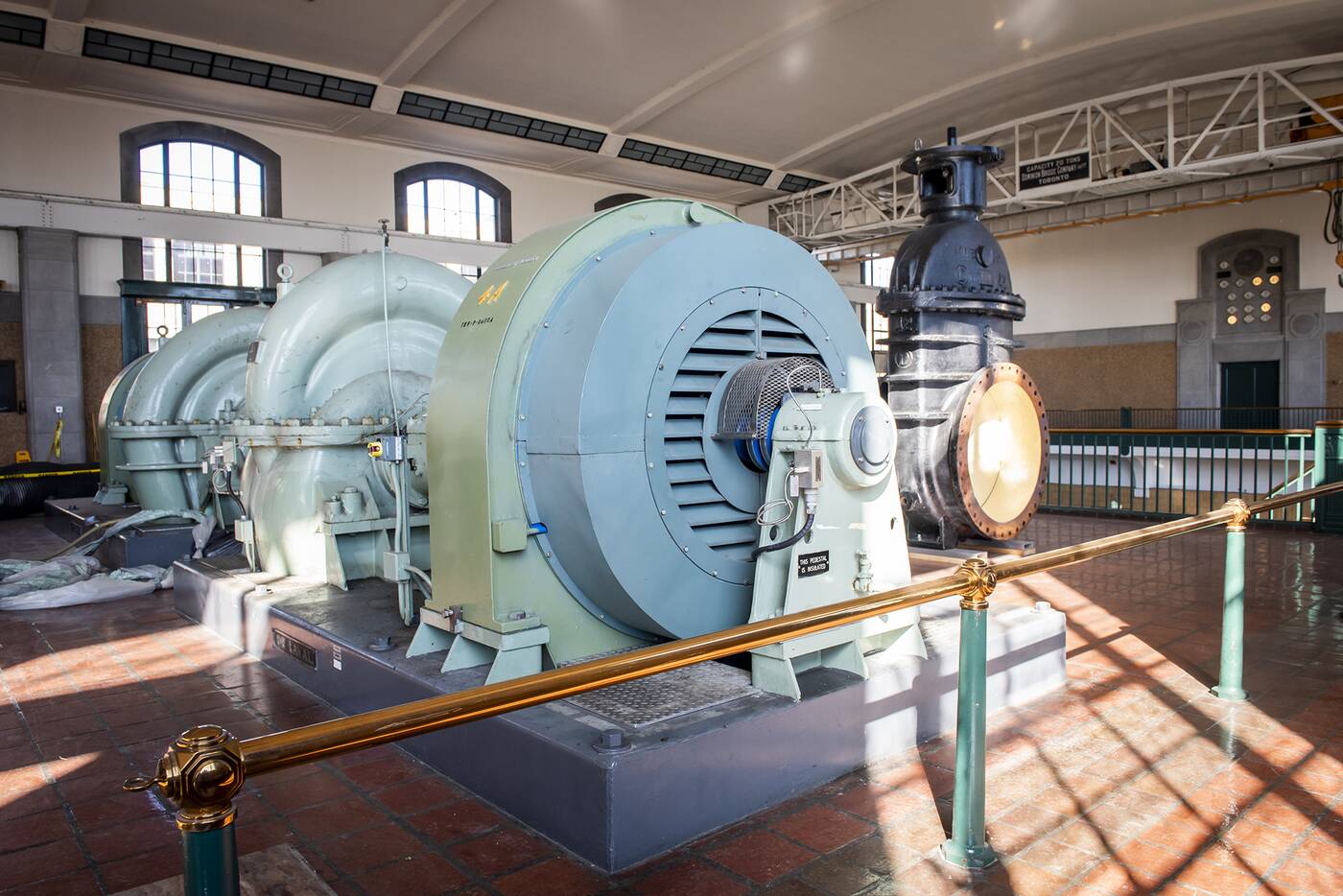

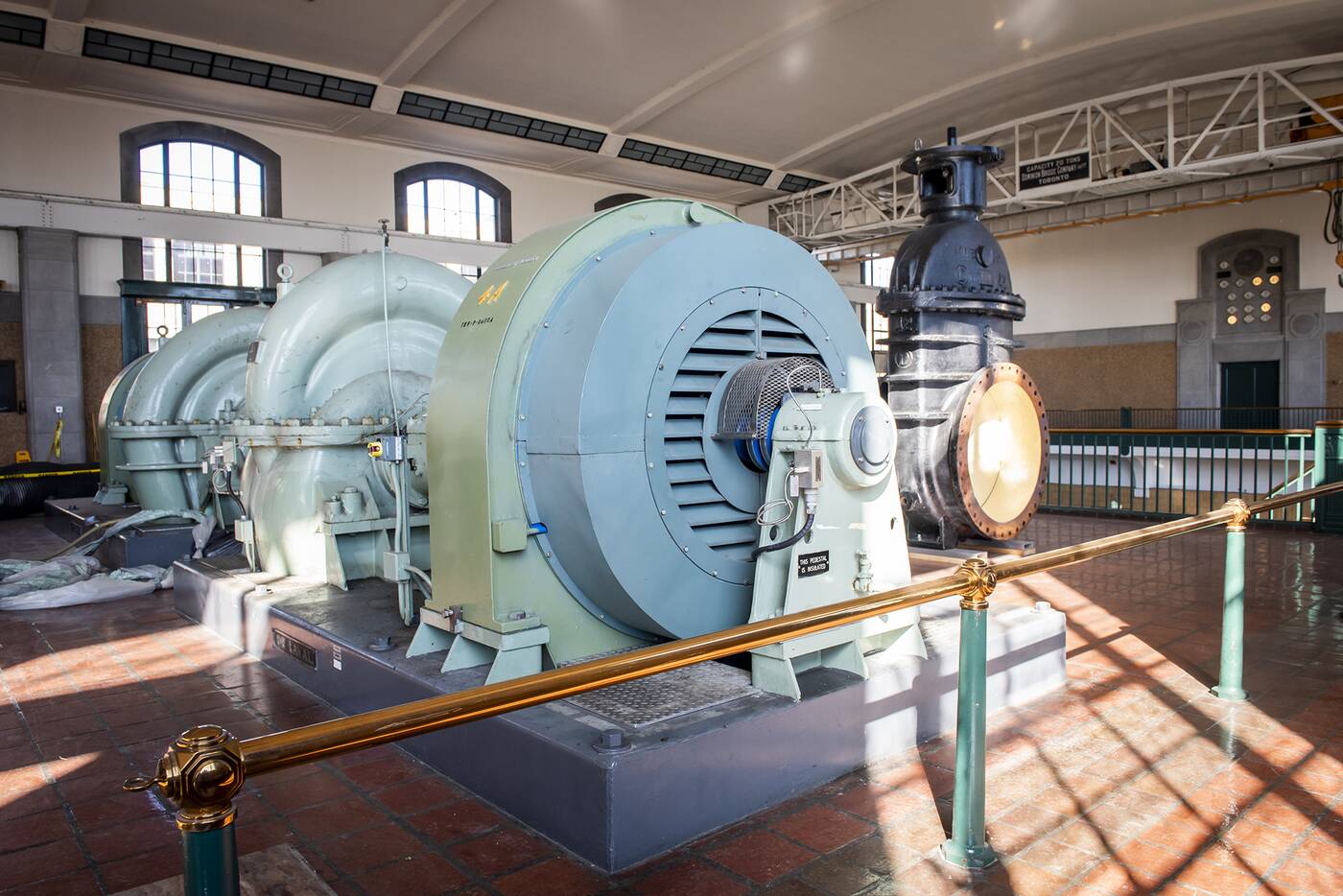

The Pump Station houses small and large pumps which direct the water flow to and from the lake.

Nearly a hundred years since its opened, the plant—made up by a filter building, service building, pumping station, and a connecting underground system—looks kind of like how you'd expect our water to taste: pristine.

In the background, you can see the limestone panel, which resembles an elevator.

Marble, brass railings, green stones and terrazzo tiles make up the building's vast halls and rounded arches. It's an enviable workplace, for the mere 30-something employees, mostly plant technicians, that work there.

Gordon Mitchell, who has been the plant manager since 2014, and working at Toronto Water since the 1990s, emphasizes the importance of maintaining old parts of the plant without building on top of it.

The marble signal pylon in the Filter Building still lights up.

He's recently overseen a new coat of seafoam green paint in the pumping station—with its soaring plaster ceiling, Queenston limestone, and herringbone tilework—that's refreshed the numbered pumps.

A limestone signal panel on the second floor of the eastern end remains from the original build, with numbers that light up, depending which pumps are operating.

Taps in the staff room show the water quality in its different stages at the plant.

Head here just once during Doors Open (the only time the R.C. Harris opens to the public) and you'll long for the days when the plant still opened weekly on Saturdays, before security-related fears of the Gulf War, then 9/11, closed it off for good.

The galleries which hold 20 filters are off-limits.

Features like a carved fountain in the Pumping Station and the largely ornamental marble signal pylon in the Filter Building are big highlights. But my favourite part is definitely the two-storey window that offers a seriously breathtaking view of Lake Ontario.

The Filter Building is home to 20 filters, which can be accessed via their original doors, made with several different types of marble. Unfortunately guests of Doors Open aren't granted into the actual filter galleries, which feel otherwordly.

Sludge cakes are essentially soil that's taken from the backwash water at the Residue Management Facility.

The newest part of the building is the Residue Management Facility, an underground facility which filters out the plant's backwash water (used to clean parts of the plant) before sending it back into Lake Ontario.

The R.C. Harris' yearly operating budget is around $12 million, which seems like pennies in the face of this massive operation that includes chlorine from Montreal, phosphoric acid from China, maintenance, and, naturally, a whopping hydro bill.

by Tanya Mok via blogTO