Nothing says Toronto like a ferry ride to the Islands on a warm summer's day. Never mind the waiting and the overcrowded terminal, every trip across the Toronto Harbour repeats a historic journey that first took place more than 180 years ago.

The original Toronto Island ferry, powered by a pair of horses walking on a treadmill, first entered commercial service in 1833, several years before the Islands were first separated from the mainland.

At the time, it was still possible to reach the lighthouse and other early buildings on foot by way of the marshes at the mouth of the Don.

The ferry service, it turns out, is actually older than the Island.

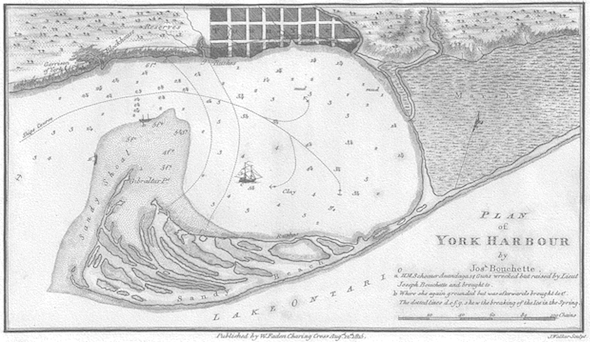

A map of the Toronto Islands when it was still connected to the mainland.

The first ever Toronto Island ferry was a simple wooden contraption that slowly paddled from the Steam Boat Wharfs at the foot of Church Street to a slip near Michael O'Connor's hotel, named The Retreat, directly across the water.

The boat was the first regularly scheduled vessel to service the Islands, even if they weren't actually separate from the mainland at the time.

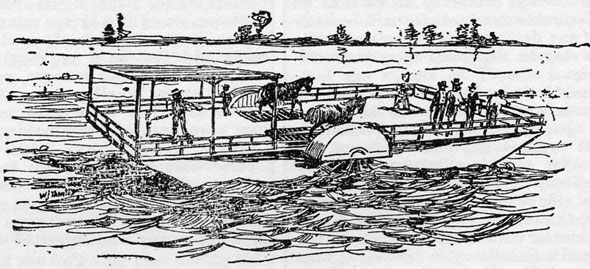

The basic machine was powered by a pair of horses walking on separate treadmills connected by a series of gears to two large paddles. A single crew member, likely O'Connor, controlled the steering at the rear while passengers rode up front on an open deck.

O'Connor, a former steward on the steam ship Canada, marketed The Retreat to "sportsmen, parties of pleasure," and those that wished to "inhale the Lake breeze." In 1833 he charged 7 1/2 pence for adults, 3 3/4 for kids. His boat ran every two or four hours every week day and Sundays.

Though it was certainly convenient, the ferry wasn't entirely necessary. Before the middle of the 19th century, it was possible to simply walk to the Islands via a narrow sand isthmus from the marshes at the mouth of the Don, as the map above illustrates.

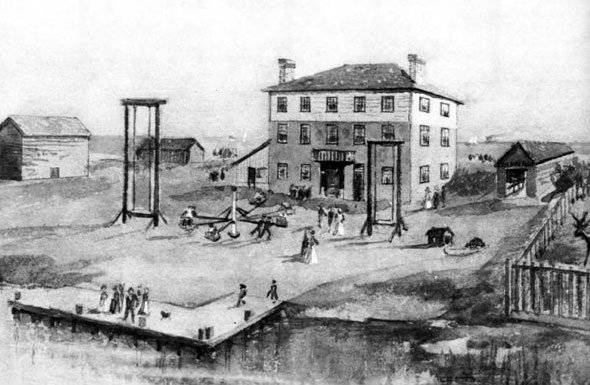

What the Toronto Islands might have once looked like.

The Eastern Gap, the 300-metre shipping passage between Ward's Island and the Port Lands, was created entirely naturally during a violent gale one spring night in 1858.

Interestingly, the area was often called an island by the town's early inhabitants prior to the storm, though it was still technically a lengthy sandbar.

Shortly after O'Connor started his hotel business, manufacturer Benjamin Knott moved his starch and soap factory to the property next door from the waterfront at Sherbourne Street. Shortly after his arrival on the Islands, Knott bought O'Connor's hotel and upgraded the ferry to a faster, four-horse vessel and slashed fares.

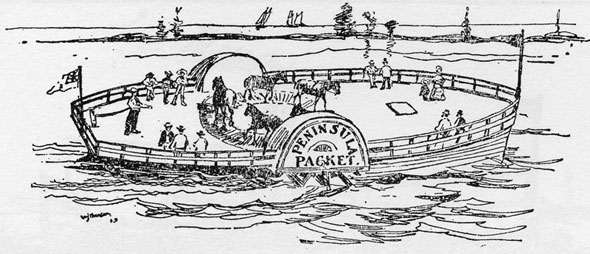

The second ferry, the Sir John of the Peninsula, named for Sir John Moore, a British army officer who had led O'Connor in battle during the Napoleonic wars, was powered by a team of horses coaxed in a circular motion on a single, large turntable.

Waiting for the Toronto Islands ferry in front of the Privat hotel.

Needless to say the journey would have taken considerably longer than it does today - the Islands used to be further away (infill has actually moved the city almost half a kilometre closer in places) and horse powered vessels tended to move quite slowly.

Knott's ownership of the hotel didn't last long. He sold up to another group of entrepreneurs, Anderton and Palin, who switched the name to the Peninsula Hotel. They fitted the place out with "neat and comfortable furniture ... a larder stocked with game, etc., in season, and choice wines."

The pair purchased the city's first steam-powered Island ferry, aptly naming it the Toronto. It was 19-metres long with a "commodious deck cabin" and harnessed a boiler capable of producing fourteen horsepower.

For reason that aren't clear, the Toronto didn't stay on the water long. As Mike Filey notes in his history of the Island ferries, the vessel was removed from service and auctioned that same year, sending travel to the idyllic outpost back to animal power.

By this time the Toronto Islands were becoming a popular destination for day-trippers. As a result, the city had established a toll of between four and six pence for each horse-drawn buggy that wished to use the trail along the isthmus and bypass the water crossing.

The remote location and verdant surroundings also made an ideal retreat for those wanting to escape the sick city during a pair of deadly cholera outbreaks in 1832 and 1834.

As fears over further deaths lingered, Charles Poulett Thompson, a wealthy citizen and future governor of the Province of Canada, bought the hotel from Anderton and Palin as a personal resort, leasing it to Louis Privat less than a decade later in 1843.

Back on the mainland, 1,000 people succumbed to the illness.

An illustration of an early ferry.

Privat purchased the Peninsula Packet, an open-deck boat drawn by John Ross Robertson in his book Landmarks of Toronto, and converted it from steam to horse power.

The Packet originally used two horses but was eventually upgraded to include room for at least four based on Robertson's sketches.

At the same time, the Privat hotel sprouted enticing new features: a merry-go-round, swings, a bowling alley, a small zoo, and pasture land for visiting horses and cattle.

In an ad for the business, Privat declared cattle would be permitted aboard the first crossing each day so that local farmers could take advantage of the unspoiled pasture.

With horse power waning and steamers becoming more common on the great lakes, Privat commissioned James Good, a foundry owner at Queen and Yonge, to build the first purposed-built Island steamer.

The 25-horsepower Victoria launched in 1850 and was accompanied by a sister ship, the Citizen, in 1853 when John Quinn became sixth owner of the hotel. Double the vessels meant half the wait, and the schedule was soon listing departures every 30 minutes.

An illustration of an early ferry.

It was around this time that passenger shipping in Toronto began to significantly pick up. A rival service run by a Captain Robert Moodie lured customers off the Victoria and the Citizen with faster crossing times. In response, Quinn introduced a third ship, the Welland.

By 1857, however, tickets could be shared between any of the four ferries. The arrival of Moodie's Lady Head later that year boosted the private flotilla to 5.

Then in 1858 the storm that permanently severed the Toronto Island's tenuous connection to the mainland swept through the city. The winds pummeled the basic wooden structure of Quinn's hotel until it was simply "borne away by the waves," according to a newspaper report.

Quinn managed to salvage some furniture and, happily, his family, but the building was a write-off. "He is said to be a heavy loser." the Leader reported on April 14, 1858. The only buildings left standing on the Island was the Gibraltar Point lighthouse and the lighthouse keeper's cottage.

Ironically, the storm that eliminated the Island ferries' road competition destroyed one of the fleet's major destinations. As history shows, passenger traffic sustained and the call of Toronto's offshore destination continues unabated.

by Chris Bateman via blogTO

No comments:

Post a Comment