It took just minutes for the S. S. Noronic to erupt into a blistering inferno that lit up the late-summer Toronto night in the early hours of September 17, 1949.

In just a couple of hours the racing, white-hot fire had claimed more than a hundred lives and gutted the ship, leaving the warped metal hull of the vast ship resting on the bottom of the shallow lake bed.

In the aftermath, the ship's crew, dangerous design, and lack of safety features would come under harsh criticism from the public and federal investigators.

As a result of the disaster many old passenger ships would be forced out of service on Lake Ontario. The Noronic disaster remains one of the deadliest incidents in the history of Toronto.

Passengers aboard the S.S. Noronic.

The S. S. Noronic was completed in 1913 by the Western Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company at Port Arthur (Thunder Bay), Ontario for the Northern Navigation Company. Its distinctive short prow and single, aft funnel made it relatively easy to identify on the water.

The 6,905-ton vessel embarked on its delayed maiden voyage late that year, showing off its wooden interior complete with ballroom, library, beauty salon, music room, and full orchestra to entertain the capacity 600 passengers.

Interestingly, the Noronic was unable to leave the ship yard on schedule because of the "Big Blow" of 1913, a violent winter storm that battered the Great Lakes, wrecking or stranding a total 38 ships.

Winds in excess of 128 kilometres an hour brought sudden snow storms and gigantic rolling waves.

Serving as a cruiser, the ship made the majority of its income during the summer taking those with enough cash on pleasure trips between major ports on the great lakes.

In the off-season, the Noronic - later owned by Canada Steamship Lines - made several journeys from Detroit through the Thousand Islands via Toronto.

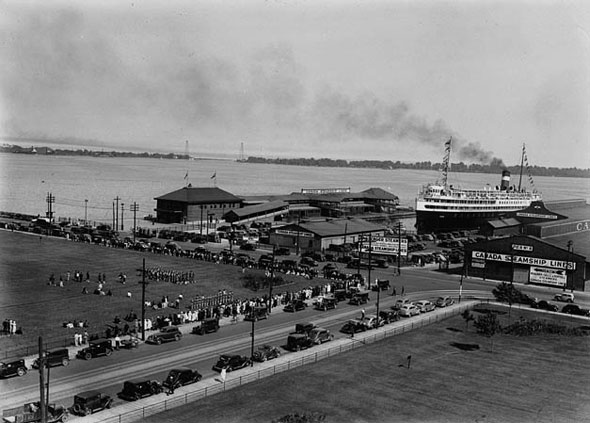

The S.S. Noronic docked on the waterfront.

On September 14, 1949, the Noronic was moored for the night at Pier 9 in Toronto close to the present-day ferry terminal. With the cool late-summer breeze blowing across its decks, only a few of its 131 crew and a handful of 574 passengers remained awake on the vessel.

At 2:30 a.m., passenger Don Church reported seeing smoke billowing under a locked linen closet on C-deck, roughly in the middle of the vessel, and alerted bellboy Earnest O'Neil.

Without sounding the fire alarm - presumably because he wasn't sure if the fire was substantial enough - O'Neil opened the closet, releasing a sudden, powerful backdraft. In seconds, the polished wood interior of the hallway was on fire. All across the ship passengers remained asleep.

O'Neil, Church and another crew member initially attempted to extinguish the flames themselves but were soon forced back by the terrifying intensity of the fire.

The ship's distress whistle sounded eight minutes after the fire had spilled from the linen closet but by this time several decks were already alight.

By chance, a worker from the New Toronto Goodyear Tire factory heading home after the late shift happened to be passing as the distress whistle cut the quiet night.

Realizing just two gangplanks were attached to the shore, Donald Williamson pushed a painting rig in place to help stranded passengers escape. By the time the first emergency services arrived, terrified, burning passengers were already leaping into the oily lake water.

An illustration of the S.S. Noronic on Lake Superior.

The flames had already breached the top deck and were almost as tall as the mast. The first fire pumper arrived at 2:41 a.m. - 11 minutes after the fire was released.

Fire-fighting boats also arrived on the scene but many passengers remained trapped within the vessel by burning stairwells and disorientating walls of smoke.

Authorities smashed portholes and attached ladders to the hull while the screams of burning passengers trapped within the craft grew louder.

As panic increasingly took hold in the face of the blinding flames, passengers began to leap to their death onto the concrete dockside and overwhelm the few escape routes.

One wooden ladder tied to the side of the ship snapped under a crush of escapees, sending women falling into the obsidian water below.

20 minutes after the first alarm, the metal structure of the Noronic was white hot and the melting metal sent the decks collapsing in on each-other.

So much water had been dumped on the vessel by this point that it had begun to lean toward the pier. It would take two full hours before the flames could be extinguished.

The aftermath of the fire on the S.S. Noronic.

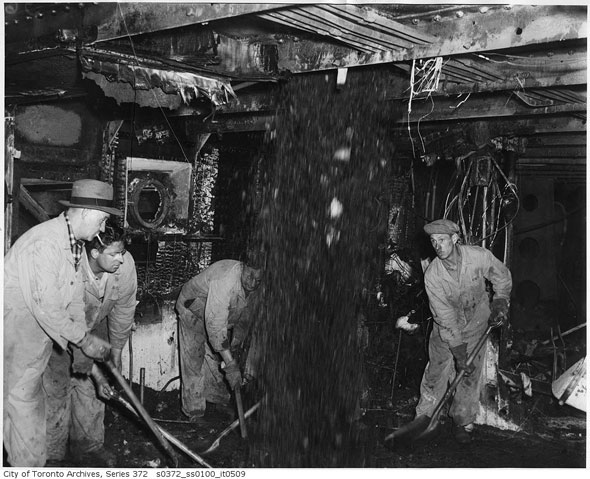

At 7:00 a.m. the gruesome task of recovering the bodies began in earnest. Crews found blackened skeletons lining the hallway - some locked in embrace - while others were found still in their beds.

It's believed many of the remains were simply vaporized. Most deaths were attributed to suffocation, crushing or burns. One person drowned after leaping into the lake.

The near-impossible task of putting a name to each of the incinerated bodies - the vast majority of whom were American - fell to Ontario's fledgling Medical Identification Committee who meticulously examined x-ray records to piece together the final list of the deceased.

All but one of the roughly 139 deaths - the number has never been precisely pinned down despite the best efforts of investigators - were passengers.

The one crew member to perish was Louisa Clarissa Dusten, a Canadian who was injured in the accident and later died on Thanksgiving Day.

The crew were severely criticized for their handling of the fire in the immediate aftermath. Many fled on seeing the flames and failed to wake sleeping passengers.

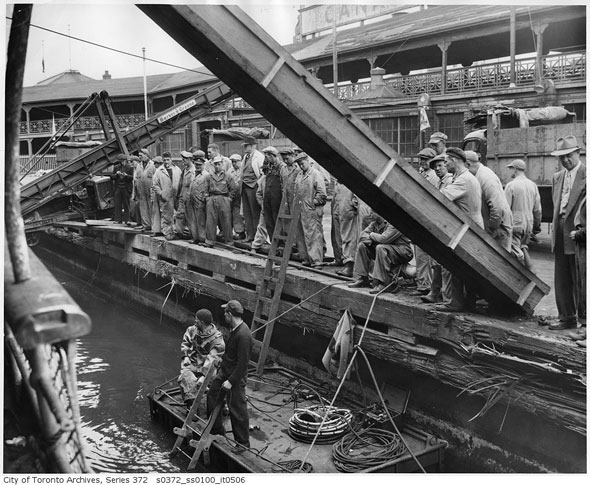

Investigators line the dock before entering the hull of the Noronic.

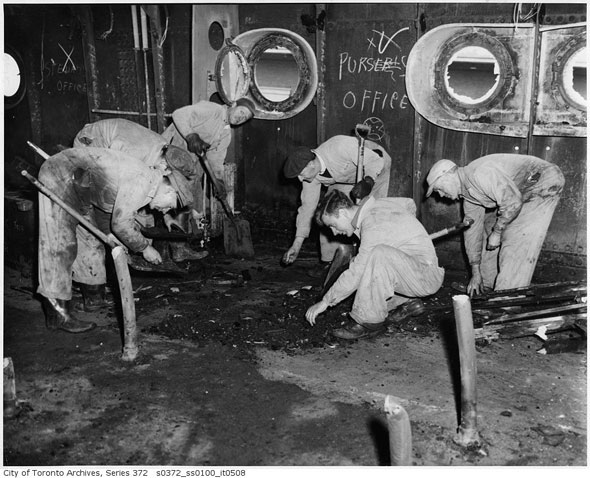

A federal inquiry by the Kellock Commission concluded that the fire was started by a discarded cigarette, possibly by someone loading the linen closet, but no-one was ever charged with causing the accident.

Workers pick through the fragile remains of the gutted interior.

The investigation also found that no crew member had contacted the fire department in the crucial first minutes of the blaze.

Investigating an area of interest in what was the purser's office.

In contrast, the actions of the Noronic's captain, William Taylor, were praised. Taylor smashed portholes and lowered numerous passengers to safety.

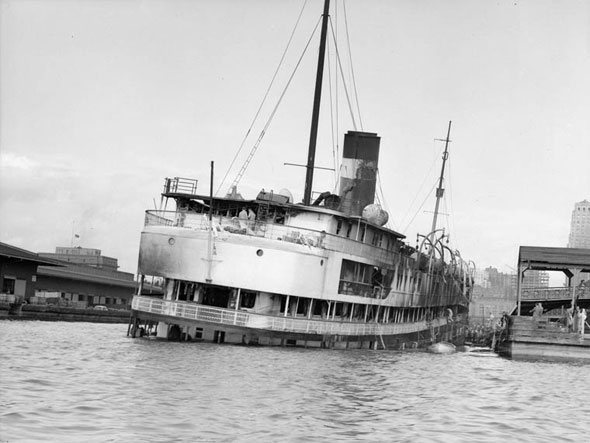

The S.S. Noronic partially sunken after the fire.

Canada Steamship Lines suspected arson in the fire, a notion supported by a similar linen closet blaze aboard the Quebec in 1950. The sunken hull of the Noronic was partially dismantled at the scene and the rest was towed to Hamilton and scrapped.

A memorial to those who lost their lives on the S.S. Noronic.

CSL would eventually pay out roughly $2 million in compensation. As a result of the disaster, materials such as wood were restricted in the construction of lake-going vessels.

Fire-proof bulkheads, fire extinguishers, automatic alarms, and sprinkler systems became mandatory. The Noronic's legacy is improved maritime safety for all.

by Chris Bateman via blogTO

No comments:

Post a Comment